By Casey Neill

PRECEDE: Mem Fox’s books have touched most Australians over the past 40 years.

The Adelaide-based author’s first book is probably still her most recognisable: Possum Magic.

Reporter Casey Neill spoke to the witty and warm Mem with her copy – a fourth birthday gift from the early 90s that now sits on her own daughter’s book shelf – beside her.

Possum Magic has unlikely origins in the King James Bible and London’s theatre scene.

Mem Fox’s Australian literary classic has been captivating children in print since 1983 – only after publishers rejected the ‘quintessential quest’ tale nine times in five years.

She puts its enduring success firstly down to the illustrations.

“We know that the pictures of any picture book are half the book,” she said.

“People often ignore that the pictures in Possum Magic are sublime.

“Julie (Vivas) doesn’t get enough credit.”

It’s also “very, very Australian” and “the last thing is because the rhythm of the language in Possum Magic is so alluring”.

The 10th publisher to see Possum Magic told Mem to cut it by two thirds, and “write lyrically, make music with the words”.

“I knew how to make it musical because I had been to drama school for three years in the mid-60s in London,” Mem said.

“I had also grown up on a mission in Africa so I was very familiar with the King James Bible.

“All of that was in the marrow of my bones.

“I had Shakespeare, I had the bible, and I also had Dr Seuss.

“I think I started writing Possum Magic when my daughter was 7, so we’d gone through seven years of Dr Seuss. I knew so many of his books by heart. Dr Seuss never gets it wrong.”

The King James Bible perhaps had the strongest influence – without Mem even noticing until six years later.

“When I was at drama school, all of us had to choose a bible story – King James Version – and learn it and tell it in a way that was not like a preacher,” she said.

“I chose the story of Ruth, which starts off, ‘Now it came to pass in the days when the judges ruled that there was a famine in the land…’.

“I copied the rhyme of those first few paragraphs for the start of Possum Magic.

“Beat for beat it’s the same.

“The rhythm is so comforting. It calms the soul.”

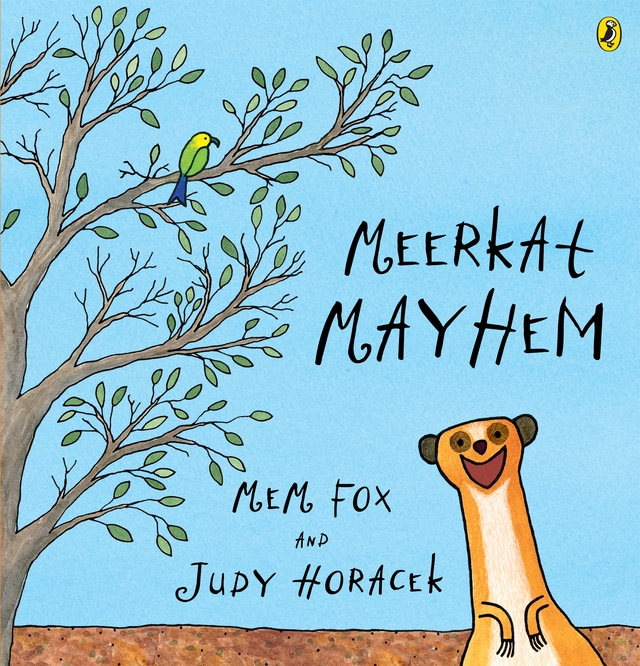

Mem’s latest book, Meerkat Mayhem, also has unlikely origins.

“I’m a constant declutterer. I’m the absolute polar opposite of a hoarder,” she said.

“I’m always throwing things out.

“I was going through a book shelf of storybooks – I was a storyteller before I was a writer.

“I had a very old book of stories – a hardback book, yellowed, you could barely read it – called Little Stories for Children.

“I looked back through it and thought ‘I can’t throw this book away’.”

Inside was folk tale The Great Big Enormous Turnip.

“The farmer grows a turnip so big he can’t pull it up,” she said.

So he calls for help from his wife, his son, and his daughter…

“It builds up, and finally up comes the turnip and they cook it for supper,” Mem said.

She regularly encountered meerkats while growing up in Africa, and easily imagined one eating too much and getting stuck in the sand.

She added a host of other African animals from her childhood and Meerkat Mayhem took shape.

“I loved creating the character of the meerkat,” Mem said.

“He’s not just a cardboard cutout meerkat.

“He is hilarious. He’s a real cool dude.”

She said Meerkat Mayhem could be her penultimate book.

“I have very few ideas – fewer and fewer,” she said.

“My next book – which is being illustrated next year and will come out in 2026 – that book may be my last book, which is OK.

“I turn 80 in 2026.”

Mem has no plans to give up writing, though she only puts pen to paper when inspiration strikes.

“If you’ve got an idea gnawing away at you, it’s irritating not to deal with it,” she said.

“If you haven’t got an idea it’s not a problem.

“If I’m not writing, it doesn’t matter to me at all.

“I don’t write for months on end.

“I am working on a story at the moment. I’ve got the word count right, it’s got repetition, it will interest little boys in particular…but when you write a book, there has to be a change in a child’s heart from the first word to the last.”

The reader needs to be excited, laughing, thoughtful, reflective, grossed out, or even frightened, she said.

“I haven’t got the emotion in the story yet. I think I will persevere,” she said.

“If you’ve been given a gift and you don’t use it, that’s very ungrateful.

“I‘ve been given a gift.

“I feel that I have to use it until the last.”

Writing is Mem’s gift but it’s her second love. Her first is teaching.

Given her passion for helping kids to read, does she consider literacy when she writes?

“It’s never front of mind, but I’m always pleased when I’ve written a book that I know is going to aid literacy,” Mem said.

“If I wrote with the aim of making kids literate I would write a woke book that was anodyne, without character.

“It’s why school readers are the worst books.

“They’re absolutely dead. They’re totally without life.”

Similarly, Mem hasn’t written any of her books with her daughter or grandson, now aged 14, in mind.

“I think that would be too particular; I have to write for everybody,” she said.

“But they might have provided the idea for a book.”

For example, she wrote Time for Bed in 1993 to ‘mesmerise’ children to sleep.

“The idea for that came from my daughter’s early life,” she said.

“She was a shocker about going to sleep.

“If only I had a book that mesmerised her…by 1993 she was 22.”

Another of Mem’s mesmersising tales is Where is the Green Sheep?, which celebrated its 20th anniversary in 2024.

“That took 11 months to write and it’s 190 words, because of the rhyme scheme,” she said.

“The rhythm has to be perfect, the beat has to fall in the right place.

“Otherwise you’re forcing a rhyme.

“And not only did line B have to rhyme with D, but also the first two lines had to connect with each other.”

Like bath and bed, moon and stars, and up and down.

“That had to happen all the way through in every verse,” Mem said.

“It’s worth persevering with the rhyme because when you don’t persevere with the rhythm and get it correct the book dies – it just dies.

“Kids don’t like reading it. Parents don’t like it, teachers don’t like it.”

Anybody who’s relayed the sheep shenanigans to a child would agree the result was worth the effort.