By Casey Neill

A Hoppers Crossing psychologist says a little bit of hope can keep kids on track.

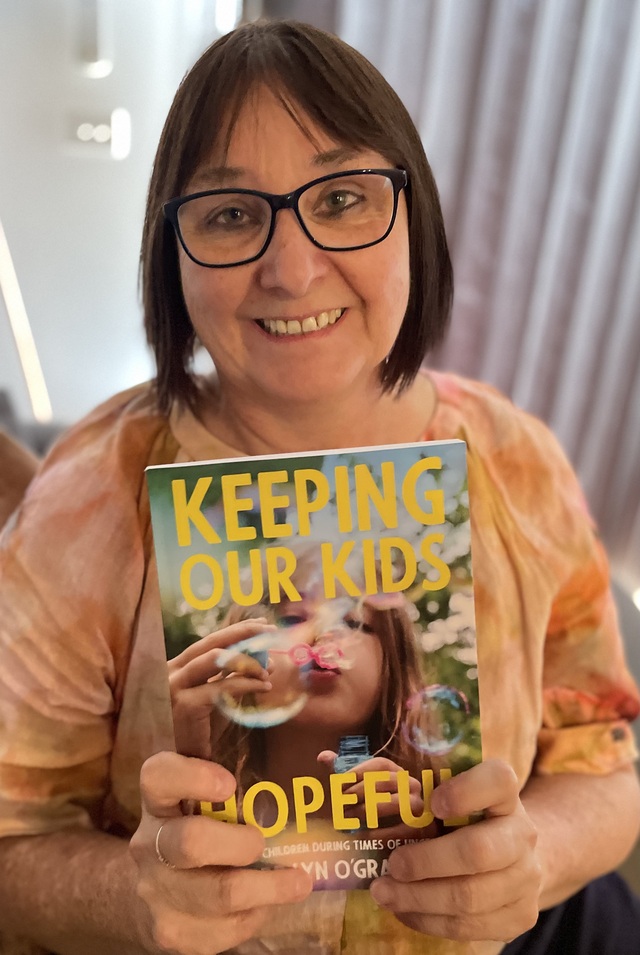

Dr Lyn O’Grady has dedicated more than 30 years to enhancing mental health and wellbeing for children, young people, and their families.

Her new book, Keeping Our Kids Hopeful: Parenting Children During Times of Uncertainty, delves into what drives us to face each new day – hope and confidence in the future.

“A loss of hope is where we become most stuck,” she said.

The book explores how this sense of hope can be fostered in children, even amid uncertainties and challenges.

“It’s for parents of primary school-aged children, really aiming to help parents understand the uncertainty and all the different things their kids might be facing, and to bring an element of hope to that,” Dr O’Grady said.

“How do we be hopeful in this space and work out how we can be hopeful as role models?”

In 2020, Dr O’Grady wrote Keeping Our Kids Alive: Parenting a Suicidal Young person.

Then she took a step back. Why wait until teens were at breaking point?

“I was very aware from my work that sometimes children had been aware of suicide but it didn’t become apparent to their parents until they were teenagers,” she said.

So she set out to provide parents with early intervention tactics and a preventative approach.

Dr O’Grady said suicide represented a loss of hope.

“It made sense to be thinking of how to embrace hope,” she said.

A consistent theme throughout the book is adults listening to children, giving children hope they’re being heard.

She said kids had lots of ideas that adults – parents, teachers, etcetera – weren’t really tuning into or really hearing. Tune into your child and work out what to do together.

“That again makes people feel hopeful,” Dr O’Grady said.

Modelling confidence is another key way to give children confidence in themselves.

“Parents have to work out this stuff first,” she said.

“If they get their own support then they’re better equipped to support the child.”

Acknowledging a child’s concern is also key.

“Sometimes parents can be dismissive of what children’s worries are,” Dr O’Grady said.

“It is about validating these worries and trying to make sense of it for yourself and being able to face it together.

“What are some of the things we can do as a family? What are some actions that we can take?”

Parents need to acknowledge that the big things exist.

“Deaths, separations, can create feelings of being less hopeful, or uncertain, or stressed,” Dr O’Grady said.

“It’s about normalising that distress and recognising children’s responses to it as being really normal.”