Despite Australia being a world leader for successful transplant outcomes, the Royal Children’s Hospital says there are more children on the waiting list for transplants than there are organs available. Fatima Halloum speaks to the family of an organ recipient about the life-changing procedure.

Zooming down slides at playgrounds and splashing in the shallows of a public pool are some of the simple joys of childhood.

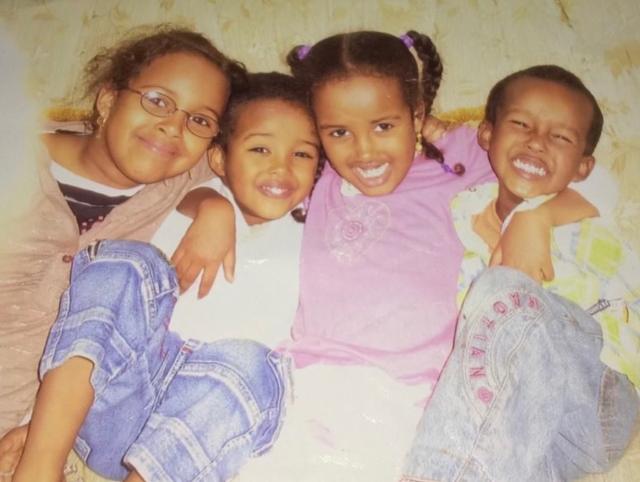

At only six-years-old, Hussein Ahmed knew he couldn’t do what other kids could.

His older sister Ikram said her brother was desperate to live a normal life.

“He tended to attract a lot of attention, and he didn’t like that at all. He didn’t like people kind of treating him differently or just singling him out,” she said.

There are some illnesses that are easier to hide, but when Hussein was diagnosed with nephronophthisis in 2013 and his kidneys began declining, doctors attached a nasogastric tube to the young boy.

“Essentially, it’s a tube through his nose which goes all the way to his stomach, and he had nutrients that he took at night that helped him grow, because he wasn’t growing,” Ikram said.

Sleepless nights and constant trips to the hospital became normal in the Truganina family’s household.

Ikram said her brother’s kidney function levels rapidly decreased, and he was put on dialysis for about two years.

“He was always aware of his condition, he would take everything as it goes,” she said.

“He’s a very firm believer that God does not burden a soul beyond what it can bear.”

When Hussein was about eight years old, his condition further worsened, and he was placed on a waiting list for a new kidney

Four years later, Ikram was startled awake by her mother’s screams in the living room.

“I wanted to see what was going on and I just saw a massive smile on her face, but like, tears quickly coming down from her eyes,” she said.

“It was like, ‘is it possible?’ and then we found out that obviously she got the call.”

Not only was Hussein finally going to receive a kidney, he was scheduled for surgery that same day.

“We were just crying out of pure excitement and happiness,” Ikram said.

That day was the first time Hussein cried, too.

“We don’t know who the organ donor is, but we’re just obviously really grateful…always keeping them in our dua (prayers),” she said.

Hussein’s experience inspired Ikram to study nursing and register as an organ donor.

“I’d love to help people as much as they’ve helped my family, and sort of repay that favour,” she said.

“Your registration as an organ donor can have a major effect on a person’s life.”

DonateLife state medical director Rohit D’Costa is renewing calls for people to sign up.

“We’ve seen about a 25 per cent decrease in donation and transplantation over the past two years due to the impacts of Covid-19,” he said.

“This is why it’s never been more important to encourage more people in the community to register as organ and tissue donors and to have the conversation with family.”

Dr D’Costa said about 1750 Australians were on the organ transplant list, an additional 13,000 people on dialysis who could benefit from a kidney transplant, and others who required an eye or tissue to improve their quality of life.

“We know many religions and cultural groups support organ and tissue donation and we need organ and tissue donors from all these communities and cultures,” he said.

“Blood and tissue types need to match for a transplant to be successful, and while ethnicity is never a consideration in either donor or recipient selection, having more diversity in organ donors can help with finding a match.

“It doesn’t matter how old you are, your medical history, your lifestyle, what country you’re from, or how healthy you are – you can still register as an organ and tissue donor. Even if you’ve had Covid or the flu, you can register.”

Hussein is now 15-years-old, and Ikram is in her last year of studying nursing.

She said the selfless act of a donor meant her younger brother got to experience life.